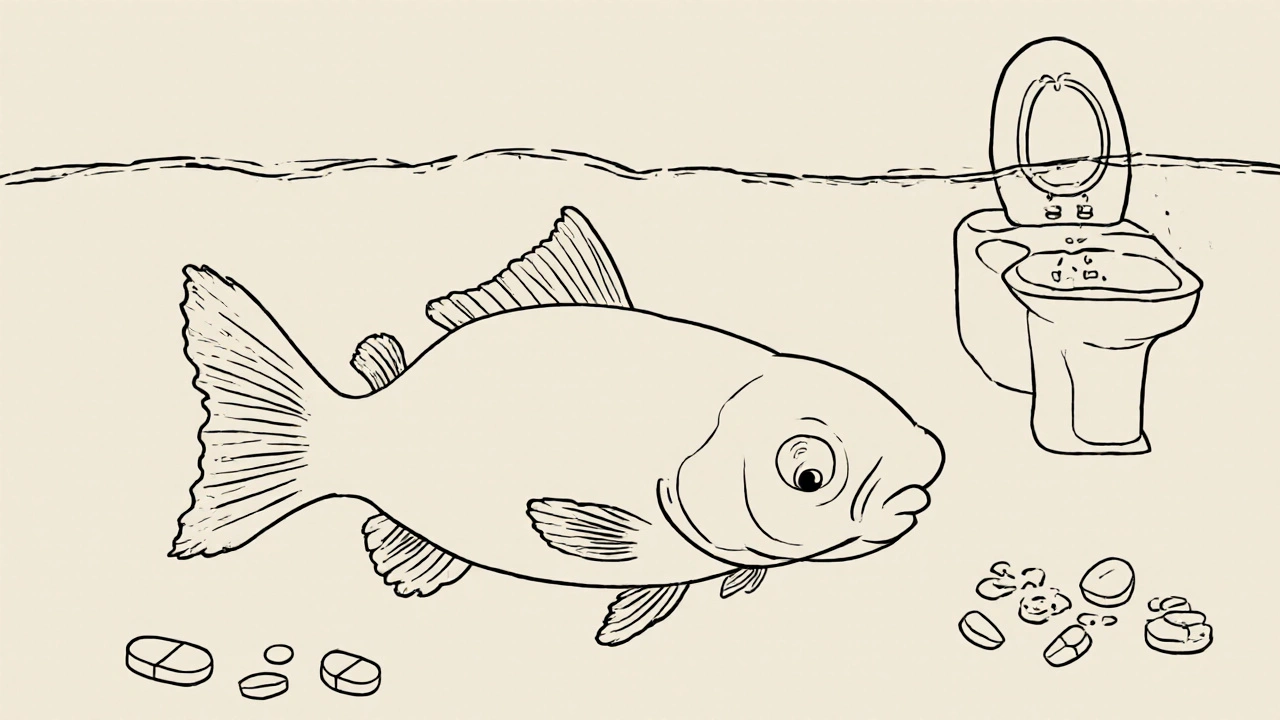

Every year, millions of unused or expired pills end up in toilets and sinks across the UK and beyond. It seems harmless-just flush it away, right? But that small act contributes to a growing crisis: pharmaceutical pollution in our rivers, lakes, and drinking water. You won’t see it. You won’t taste it. But it’s there. And it’s changing aquatic life in ways we’re only beginning to understand.

Why Flushing Medications Is a Problem

When you flush a pill, it doesn’t vanish. It enters the wastewater system. And here’s the hard truth: most wastewater treatment plants weren’t built to remove drugs. They’re designed to catch solids, kill bacteria, and remove nutrients-not tiny chemical molecules like ibuprofen, antidepressants, or antibiotics. These compounds slip right through. Studies from the U.S. Geological Survey in the early 2000s found traces of over 100 different pharmaceuticals in 80% of tested rivers and streams. Since then, similar findings have been confirmed in Europe, including the UK. Even though concentrations are low-often measured in nanograms per litre-they’re persistent. And they add up. Fish are showing signs of disruption. Male fish have been found developing female characteristics due to estrogen-like compounds from birth control pills. Antibiotics in water are helping resistant bacteria grow, making infections harder to treat in humans and animals alike. One study found acetaminophen at over 100,000 nanograms per litre in landfill leachate. That’s not a typo. That’s a warning.Where Do Medications Actually Go?

There are three main paths for unused meds:- Flushing-direct entry into waterways

- Trash disposal-ends up in landfills, where chemicals can leak into groundwater

- Excretion-your body doesn’t absorb all the drug; what’s left comes out in urine

The Best Alternative: Take-Back Programs

The cleanest, safest way to dispose of unused medications is through a take-back program. These are drop-off points-often at pharmacies, hospitals, or police stations-where you can hand over old pills, liquids, or patches without a trace. In the UK, the NHS and local councils run periodic drug take-back days, and some pharmacies participate in permanent collection bins. Bristol has several drop-off locations, including pharmacies on Whiteladies Road and Clifton Down. You don’t need a prescription to use them. Just bring the meds, no packaging needed. These programs are effective. They prevent drugs from entering water or landfills. They also reduce the risk of misuse. But they’re not everywhere. Only about 30% of people in the UK know where their nearest drop-off point is. And many rural areas have no access at all.

What If There’s No Take-Back Option?

If you can’t get to a take-back location, here’s what the EPA and UK environmental agencies recommend:- Take the medication out of its original bottle.

- Mix it with something unappealing-used coffee grounds, cat litter, or dirt.

- Put the mixture in a sealed container-a jar or plastic bag.

- Throw it in the household trash.

Why Don’t More People Use Take-Back Programs?

Lack of awareness is the biggest barrier. Many think expired meds are harmless. Others believe flushing is the easiest option. Some don’t know where to go. A 2021 survey found that nearly half of UK adults still keep old medications in their medicine cabinets. There’s also confusion around the FDA’s flush list. People hear “some drugs can be flushed” and assume it applies to all. It doesn’t. Only 15 specific high-risk opioids are on the list. Everything else? Keep it out of the toilet. And let’s be honest-driving 20 minutes to drop off a box of old painkillers feels like a hassle. But so does living in a world where fish are turning female and antibiotics stop working.

What’s Being Done About It?

The EU has made progress. Since 2022, 16 member states require pharmaceutical companies to fund and manage take-back programs. In the UK, the NHS is slowly expanding collection points, and some pharmacies now offer mail-back envelopes for unused meds. California passed a law in 2024 requiring pharmacies to give disposal instructions with every prescription. The UK is watching closely. There’s growing pressure to make take-back programs as common as recycling bins. Meanwhile, scientists are testing new water treatment methods-ozone filtration, activated carbon-that can remove up to 95% of pharmaceuticals. But these systems cost hundreds of thousands of pounds to install. They’re not coming to your local treatment plant anytime soon. The real solution? Prevention. Prescribing fewer pills. Educating patients. Ending the culture of hoarding meds “just in case.”What You Can Do Today

You don’t need a policy change to make a difference. Here’s your action list:- Check your medicine cabinet. Remove anything expired or no longer needed.

- Search for your nearest take-back location using the NHS website or your local council’s environmental page.

- If no drop-off exists, use the coffee grounds method. Seal it. Trash it.

- Don’t flush-not even one pill.

- Ask your pharmacist: “Do you take back unused medications?” If they say no, ask why. Push for change.

Final Thought: This Isn’t Just About Water

This issue isn’t just environmental. It’s public health. It’s ethics. It’s responsibility. We don’t flush batteries. We don’t pour paint down the drain. We don’t dump old electronics in the bin. So why do we flush pills? Because we’ve been told it’s okay. Because we didn’t know better. Now you do. And that changes everything.Is it ever okay to flush medications down the toilet?

Only if the medication is on the FDA’s official flush list-currently only 15 high-risk opioids like fentanyl and oxycodone. These are exceptions because the risk of accidental overdose outweighs environmental concerns. For every other medication, including painkillers, antibiotics, or antidepressants, flushing is not recommended. Always check the label or ask your pharmacist first.

Where can I find a medication take-back location in the UK?

Many pharmacies, hospitals, and police stations in the UK offer take-back bins. You can search for locations using the NHS website’s “Medication Disposal” tool or your local council’s environmental services page. In Bristol, take-back points are available at several pharmacies including Boots on Whiteladies Road and the Clifton Pharmacy. Some areas also host annual drug take-back events-check your council’s calendar.

Can I dispose of liquid medications in the trash?

Yes, but not directly. Pour liquid medications into a sealable container and mix them with an absorbent material like cat litter, coffee grounds, or sawdust. Then seal the container tightly before placing it in your household trash. Never pour liquids down the sink or toilet, even if they’re expired. This prevents leaks and reduces the chance of accidental ingestion.

Why can’t wastewater treatment plants remove drugs?

Wastewater plants are designed to remove solids, bacteria, and nutrients-not tiny, stable chemical molecules like pharmaceuticals. These compounds are too small and chemically resistant to be filtered out by standard processes. Some may break down slightly, but many remain unchanged and pass through into rivers and lakes. Advanced treatments like ozone or activated carbon can remove them, but they’re expensive and not widely used.

Do expired medications lose their effectiveness and become safe to flush?

No. Expired medications don’t become harmless-they just become less effective. The chemical structure remains intact and can still pollute water. Flushing expired pills is just as harmful as flushing new ones. Always dispose of them the same way: through take-back programs or the trash with absorbent material. Never assume expiration means safety.

Are there any at-home products that destroy medications safely?

Yes, some commercial products like Drug Buster or MedTakeBack use chemical degraders to break down pills into harmless substances. But they’re expensive (around £25-£35 per unit), require careful use, and aren’t widely available in the UK. For most people, mixing with coffee grounds and trashing is simpler, cheaper, and just as effective at preventing environmental harm and misuse.

How does pharmaceutical pollution affect human health?

Direct health effects from trace amounts in drinking water are still being studied, but the bigger risk is indirect. Antibiotics in water contribute to drug-resistant bacteria, making infections harder to treat. Endocrine disruptors may affect hormone systems over time. There’s also concern about biomagnification-where drugs build up in fish and then enter the human food chain. While no confirmed cases of illness from drinking water have been proven, the long-term risks are enough to justify prevention.

Comments

9 Comments

Kevin Wagner

Flushing pills is the lazy person’s way of dodging responsibility. I get it-life’s busy, your cabinet’s a graveyard of expired ibuprofen, and the nearest drop-off is 20 minutes away. But here’s the thing: if you’re too tired to mix your meds with coffee grounds, you’re too tired to be holding onto them in the first place. This isn’t rocket science. It’s basic stewardship. We don’t dump batteries in the toilet. Why the hell are we dumping antidepressants? We’re poisoning rivers so our kids won’t have to drive 15 minutes to a pharmacy. That’s not convenience-that’s cowardice.

gent wood

I live in Bristol and use the Whiteladies Road drop-off every six months-no hassle, no questions asked. The pharmacist always smiles and says, ‘Thanks for doing the right thing.’ It’s not about being perfect-it’s about being consistent. I’ve seen people dump half-empty bottles into the bin and think they’re ‘doing their bit.’ They’re not. Mixing with cat litter? That’s the bare minimum. If you’re going to bother, do it right. And if your local pharmacy doesn’t take them? Ask why. Politely. Repeatedly. Change doesn’t happen by accident.

Dilip Patel

you think this is bad?? wait till you see how much pharma waste comes from usa and germany!! we in india flush everything and still our rivers are cleaner than yours!! also why are you so obsessed with fish? they dont even feel pain like humans!! and who cares if antibiotics get into water?? we have ayurveda for that!! also my cousin in delhi takes expired paracetamol and he is 92 and still plays cricket!! so stop your western guilt trip!!

Jane Johnson

While I appreciate the intent behind this post, I must note that the assertion that pharmaceutical pollution is a 'growing crisis' lacks longitudinal peer-reviewed epidemiological data linking trace concentrations in aquatic systems to measurable human health outcomes. The precautionary principle is not a substitute for evidence. Furthermore, the recommendation to use coffee grounds as a binding agent is neither standardized nor validated by environmental toxicology protocols. I would recommend consulting the Environment Agency’s 2023 guidance on controlled pharmaceutical waste segregation.

Sean Hwang

My grandma used to keep all her meds in a shoebox under the bed. When she passed, we found 17 bottles of stuff she hadn’t taken in 5 years. I mixed it all with cat litter, sealed it in a ziplock, and tossed it. No big deal. Don’t overthink it. If you don’t have a drop-off, trash it with something gross. That’s it. No need for fancy programs or guilt trips. Just don’t flush. Ever. Even one pill.

Barry Sanders

Let’s be real: this is a first-world problem dressed up as an environmental crisis. The concentration of pharmaceuticals in water is so low it’s practically a joke. You’re more likely to die from a falling coconut than from drinking water with trace antidepressants. Meanwhile, the real pollution? Plastic microfibers, industrial runoff, coal ash. But no-let’s panic about a few nanograms of ibuprofen. Classic virtue signaling. Do something useful. Like recycling your old phone.

Chris Ashley

bro i just threw my expired Xanax in the toilet last week and now i feel guilty af. is it too late? can i undo it? i swear i thought it was fine. my roommate says i’m a monster now. help.

kshitij pandey

My village in Uttar Pradesh doesn’t have a pharmacy drop-off, but we have a system: we collect old medicines from neighbors, burn them safely in a metal drum away from water, and bury the ash. No one flushes. No one dumps. It’s simple, old-school, and works. Maybe we don’t need fancy tech. Maybe we just need to remember how to care. We’re not just saving fish-we’re saving our future. Small acts, big impact.

Brittany C

It’s worth noting that the bioaccumulation potential of certain pharmaceuticals-particularly lipophilic compounds like fluoxetine and carbamazepine-has been documented in trophic transfer studies involving invertebrates, amphibians, and piscine species. The persistence of these xenobiotics in sedimentary matrices, coupled with their endocrine-disrupting properties at sub-therapeutic thresholds, suggests a need for tiered regulatory intervention beyond consumer-level disposal protocols. The current EPA guidelines, while pragmatic, are insufficiently granular to address chronic, low-dose exposure dynamics in aquatic ecosystems.

Write a comment