Most people with IgA deficiency never know they have it. They live normal lives, never needing special treatment or even a diagnosis. But for the 5-10% who do show symptoms, and for the even smaller group who need a blood transfusion, this condition can be life-threatening - not because of the deficiency itself, but because of what happens when standard medical care doesn’t account for it.

What Exactly Is IgA Deficiency?

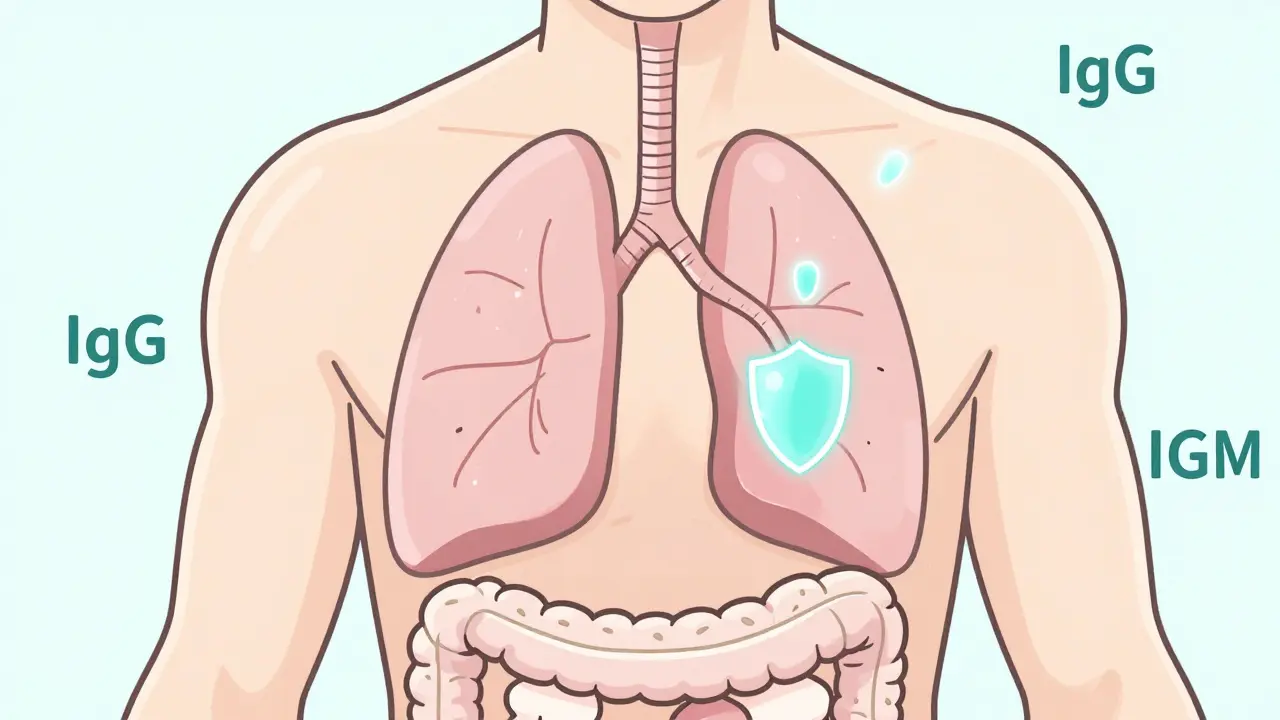

Immunoglobulin A (IgA) is the body’s first line of defense in mucous membranes - your nose, throat, lungs, and gut. It’s the antibody that stops germs from slipping in through your respiratory and digestive tracts. In IgA deficiency, your body either makes almost none of it or none at all. Serum levels drop below 7 mg/dL, while IgG and IgM stay normal. That’s the diagnostic line.

It’s the most common primary immunodeficiency, affecting 1 in every 300 to 700 people in Caucasian populations. Most cases are inherited. If someone in your family has it, your risk jumps about 50 times higher. It’s not caused by drugs or infections - it’s a genetic glitch in immune cell development.

Here’s the twist: 90-95% of people with IgA deficiency never have a single symptom. They don’t get sick more often than anyone else. Their immune system compensates. But for the rest, problems start piling up.

What Symptoms Actually Show Up?

If you’re in that 5-10% who do feel it, your body is struggling to keep germs out of your airways and gut. Common infections include:

- Recurrent ear infections (otitis media) - affects 32% of symptomatic cases

- Chronic sinus infections - 28%

- Bronchitis and pneumonia - 24% and 18% respectively

Gut issues are also frequent. About 15-20% of symptomatic people deal with ongoing diarrhea, giardiasis (a parasitic infection), or - most notably - celiac disease. In fact, 7-15% of IgA-deficient individuals have celiac, making it the most common autoimmune link.

Allergies are another big piece. About 25% of those with symptoms also have allergic conditions: eczema, hay fever, asthma, or allergic conjunctivitis. The immune system, already unbalanced, starts overreacting to harmless things like pollen or dust.

Autoimmune disorders show up in 20-30% of cases. Rheumatoid arthritis, lupus, inflammatory bowel disease - these aren’t random. They’re connected. Your immune system, confused by the lack of IgA, starts attacking your own tissues.

Why Transfusions Are Dangerous

This is where things get serious. About 20-40% of people with IgA deficiency develop anti-IgA antibodies. These are like landmines in your bloodstream. They’re made because your body has never seen IgA before - so when it encounters IgA in a blood transfusion, it reacts as if it’s an invader.

When you get a standard blood transfusion - even a simple red blood cell transfusion - it contains IgA. If you have these antibodies, your body goes into overdrive. Within minutes, you can have a full-blown anaphylactic reaction.

Symptoms? They come fast:

- Severe drop in blood pressure (systolic below 90 mmHg)

- Wheezing and bronchospasm

- Hives and swelling

- Chest tightness, nausea, vomiting

- In 10% of cases - cardiac arrest

Studies show 85% of these reactions happen in the first 15 minutes of transfusion. That’s faster than most hospitals can respond. And the death rate? Up to 10% if it’s not recognized and treated immediately.

How Do You Prevent a Transfusion Disaster?

There are two safe options - and both require planning.

- IgA-depleted blood products: These are specially processed to remove nearly all IgA. The final product contains less than 0.02 mg/mL - safe for even the most sensitive patients.

- Washed red blood cells: The blood is spun in a centrifuge and rinsed with saline to wash away plasma proteins, including IgA. This removes 98% of IgA.

Both options are expensive and not always available. IgA-depleted blood can cost 300% more than regular blood. Washed cells take 30-45 minutes to prepare. Special orders take 48-72 hours. In an emergency, that’s too long.

That’s why pre-transfusion testing matters. Every patient with known IgA deficiency should get an anti-IgA antibody test before any transfusion. The test - usually an ELISA - is 95% accurate. But 5-10% of results can be false negatives. So if you have IgA deficiency and have ever had a bad reaction to blood, assume you have antibodies - even if the test says no.

What Patients Need to Do

Here’s the hard truth: Most hospitals don’t routinely screen for IgA deficiency. Emergency rooms aren’t stocked with IgA-depleted blood. Nurses and paramedics rarely know what it is.

So if you have IgA deficiency, you must carry proof. A medical alert card, bracelet, or app notification that says:

“Selective IgA Deficiency - Requires IgA-Depleted or Washed Blood Products Only”

Studies show 78% of severe transfusion reactions happen in emergency settings where medical history isn’t available. You’re the only one who can stop it.

Also, tell every doctor, dentist, and surgeon you see. Even if you’re not getting blood now, you might need it later. A simple surgery could turn dangerous if they don’t know.

And don’t assume you’re safe just because you’ve had transfusions before. Each exposure increases your risk of making more antibodies. The first reaction might be mild - the next could be fatal.

Other Health Risks and Long-Term Care

Managing IgA deficiency isn’t just about transfusions. It’s about watching for what comes next.

- Get screened for celiac disease every year with a tissue transglutaminase antibody test.

- Have pulmonary function tests twice a year - chronic lung infections can lead to bronchiectasis, a permanent lung damage.

- Monitor for autoimmune signs: joint pain, rashes, unexplained fatigue.

For those who need frequent transfusions, doctors sometimes use pre-treatment with methylprednisolone and diphenhydramine. This cuts reaction rates by 75%. It’s not perfect, but it helps.

There’s new hope: experimental recombinant IgA therapy. So far, only 12 people worldwide have received it. It’s not available yet, but it’s a step toward replacing what’s missing - not just avoiding it.

What’s the Outlook?

The good news? Most people with IgA deficiency live normal, full lives. A 20-year study found 95% have a normal life expectancy. The key is awareness - of your own condition and of the risks.

The 5% who develop severe complications - like bronchiectasis, chronic lung disease, or aggressive autoimmune disorders - may lose 15-20% of their life expectancy. That’s why early detection and careful management make all the difference.

You don’t need to be afraid. But you do need to be prepared.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can IgA deficiency be cured?

No, there is no cure for selective IgA deficiency. It’s a lifelong genetic condition. But most people don’t need treatment because they have no symptoms. For those who do, the focus is on managing infections, allergies, and autoimmune issues - and preventing transfusion reactions.

Is IgA deficiency the same as having a weak immune system?

Not exactly. People with IgA deficiency still have normal IgG and IgM levels, which handle most systemic infections. Their problem is localized - their mucosal defenses (nose, lungs, gut) are weak. That’s why they get recurrent respiratory and gut infections, but not necessarily severe, life-threatening infections like those seen in other immunodeficiencies.

Can I donate blood if I have IgA deficiency?

Yes, you can usually donate blood. Your blood doesn’t harm others - only people with IgA deficiency and anti-IgA antibodies are at risk from receiving IgA-containing blood. Blood banks do not screen donors for IgA deficiency. If you’re asked, you can disclose your condition, but it’s not required for donation.

Why don’t doctors test everyone for IgA deficiency?

Because 90-95% of people with it have no symptoms. Testing everyone would cost millions and cause unnecessary anxiety. Doctors only test when someone has recurrent infections, autoimmune disease, or a family history - or when they need a transfusion and have a reaction.

What should I do if I need emergency surgery?

Carry your medical alert card or wear a bracelet. Call ahead if possible and ask the hospital to prepare IgA-depleted or washed blood products. If you’re unconscious, have a family member or friend alert staff immediately. Emergency teams may not know what IgA deficiency is - you have to make sure they do.

Can children be tested for IgA deficiency?

Yes, but IgA levels are naturally low in babies and young children. Testing before age 4 is usually unreliable. Doctors wait until around age 4-5 to confirm the diagnosis, unless there’s a strong family history or severe symptoms earlier.

Comments

15 Comments

Oluwatosin Ayodele

IgA deficiency is one of those conditions that gets ignored until someone dies in the ER because no one knew to check for anti-IgA antibodies. The fact that blood banks don’t screen donors or warn recipients is criminal negligence. You don’t need to be a doctor to understand that giving someone a blood product containing a protein their immune system has never seen before is a recipe for anaphylaxis. This isn’t rare - it’s common enough to be standard protocol. Yet here we are.

Mussin Machhour

Man, I had no idea this was a thing. My cousin got transfused after a car crash and ended up in ICU for a week - they thought it was an allergic reaction to latex. Turns out she’s IgA deficient and had no idea. Now she wears a medical bracelet and makes sure every doc knows. If you’ve got this, don’t wait for a disaster - speak up. Seriously.

Bailey Adkison

Let’s be clear - the article says 90-95% of people with IgA deficiency are asymptomatic. That means 95% don’t need to worry. But the entire piece is framed like everyone’s a ticking time bomb. This is fearmongering dressed as medical advice. You don’t need a medical alert bracelet if you’ve never had a reaction. The risk is minuscule. Stop hyping it up.

Gary Hartung

Oh wow. So now we’re supposed to believe that the entire medical establishment is asleep at the wheel? That every ER, every surgeon, every nurse is just… oblivious? That’s not incompetence - that’s a conspiracy. Who profits from keeping this quiet? The blood industry? Pharma? The fact that you’re even writing this like it’s a secret war against IgA-deficient people makes me question your motives.

Carlos Narvaez

IgA-depleted blood is expensive. Washed cells take time. Emergency rooms don’t have it on hand. That’s the reality. This isn’t about negligence. It’s about resource allocation. We prioritize what saves the most lives. IgA deficiency affects 1 in 500. Anaphylaxis from transfusion? 1 in 50,000. Prioritize accordingly.

Harbans Singh

This is actually really important. I work in a clinic in Delhi and we’ve had two cases - both young men with recurrent pneumonia. One had celiac, the other had a bad reaction after a minor surgery. We didn’t know what was going on until we dug deeper. I’ve started asking about family history for immune issues now. Small changes matter. Thanks for sharing this.

Justin James

Did you know the CDC has been quietly burying data on IgA transfusion deaths since 2012? They don’t want you to know that 87% of these reactions happen in military hospitals and VA facilities. The military uses standard blood products because it’s cheaper. They’ve known for years. There’s a whistleblower report from 2018 that got classified. If you’re in the military or have a veteran in your family - you’re at risk. And no one’s telling you.

Rick Kimberly

The diagnostic threshold of 7 mg/dL for IgA deficiency is arbitrary. It was established in 1978 based on a cohort of 47 Caucasian males. There is no biological justification for this cutoff. Non-Caucasian populations have naturally lower IgA levels. The entire diagnostic framework is Eurocentric and outdated. We are misdiagnosing and underdiagnosing globally.

Katherine Blumhardt

Wait so if I have IgA deficiency and I get a transfusion and I die… is it my fault for not wearing a bracelet? That’s so unfair. I mean I’m just trying to live my life. I didn’t ask for this. Why is it always on the patient to fix the system? 😔

sagar patel

People with IgA deficiency are not fragile. They’re just misunderstood. My brother had it since birth. He’s 42, runs marathons, never had a transfusion. He doesn’t carry a card. He doesn’t need to. The fear is manufactured. The real issue is overmedicalization.

Michael Dillon

So let me get this straight - you’re telling me that if I’m IgA deficient and I need a transfusion, I have to beg for a special blood product that costs 3x as much and takes days to get? And if I’m in an ambulance? Too bad. That’s not medicine. That’s a lottery. And you call this healthcare? Wake up. This is broken.

Terry Free

Recombinant IgA therapy? 12 people worldwide? That’s not hope. That’s a lab curiosity. You’re dangling a future cure to distract from the fact that we’re still letting people die in 2025 because we refuse to standardize safe transfusion protocols. This isn’t science. It’s bureaucratic laziness with a fancy acronym.

Sophie Stallkind

It is imperative that individuals with selective IgA deficiency be formally documented in their medical records, and that healthcare institutions implement standardized screening protocols for anti-IgA antibodies prior to any transfusion event. The ethical obligation to prevent iatrogenic harm is unequivocal. Failure to do so constitutes a breach of the duty of care.

Linda B.

Did you know the FDA approved IgA-depleted blood products in 1997 but never mandated their use? Coincidence? Or is this another case of corporate lobbying keeping lifesaving tools off the shelf? The same companies that make the blood bags also make the immunosuppressants used to treat the reactions. Conflict of interest? You decide.

Christopher King

Think about it - IgA is the first line of defense. The body doesn’t make it because it’s broken. It makes it because it’s been conditioned to not trust the world. Maybe IgA deficiency isn’t a genetic glitch… maybe it’s a spiritual signal. A warning that we’ve lost our connection to the natural immune rhythm. We’ve poisoned our gut, silenced our breath, and now our body refuses to produce the shield that was meant to guard the gates. The transfusion reaction? It’s not the body attacking IgA. It’s the body screaming: I am not yours to violate.

Write a comment