When you’re prescribed a combination drug-like amlodipine and benazepril for high blood pressure-you might not think twice when the pharmacy swaps the brand for a cheaper generic. But what if the doses aren’t truly the same? Or if one version absorbs differently in your body? This isn’t theoretical. It happens every day. And it’s why therapeutic equivalence in combination products isn’t just a regulatory footnote-it’s a patient safety issue.

What Therapeutic Equivalence Really Means

Therapeutic equivalence means two drug products can be swapped without changing how well they work or how safe they are. The U.S. FDA calls this the "A" rating. It’s not just about having the same active ingredients. The pills must contain the exact same amount of those ingredients, in the same form (tablet, capsule, etc.), and delivered the same way (oral, injected, etc.). They also need to meet strict standards for purity and strength. The FDA tracks over 14,000 products in its Orange Book, and about 95% are rated "A"-meaning, on paper, they’re interchangeable. But here’s the catch: that rating doesn’t guarantee identical results in every person. Especially with combination drugs. Take a product like tramadol plus acetaminophen. One component relieves pain, the other boosts it. Together, they work better than either alone. But if you switch from one generic version to another-even if both are "A" rated-the way those two drugs are released into your body might shift slightly. That’s enough to throw off the balance.Dose Equivalence Isn’t Always Additive

Many assume that if two drugs are combined, their effects just add up. But biology doesn’t work like math. In some cases, one drug can make the other stronger-or weaker. For example, sirolimus reduces vascular cell growth by nearly 70%, while topotecan hits almost 89%. If you combine them, you can’t just average the doses. You need a formula: beq(a) = CBγ(1+CAa)−1, where γ is the ratio of their effectiveness. That’s not something a pharmacist calculates on the fly. It’s something the FDA should have built into the approval process. Yet most combination products are approved based on simple bioequivalence studies done on single ingredients. The FDA doesn’t require testing the combination as a whole unless it’s a new drug. That means a generic version of a combo might be "equivalent" to the brand for each part individually-but not as a unit. And that’s where problems start.The NTI Problem: When Small Changes Matter

Narrow therapeutic index (NTI) drugs are the most dangerous to swap. These are medications where the difference between a helpful dose and a toxic one is tiny. Think warfarin, levothyroxine, or phenytoin. Now imagine one of those is part of a combo drug. A 5% change in absorption might be fine for most meds. But for NTI drugs, that’s enough to cause a clot, a seizure, or a thyroid crisis. A 2018 study found that 12% of patients switching between different generic levothyroxine products-even ones rated "A"-had abnormal thyroid levels. That’s not a glitch. That’s systemic. The FDA requires a tighter bioequivalence range (90-111%) for NTI drugs instead of the usual 80-125%. But when those drugs are combined, that standard often gets ignored. The combination is approved based on the simpler, looser rules.Why Generic Substitutions Go Wrong

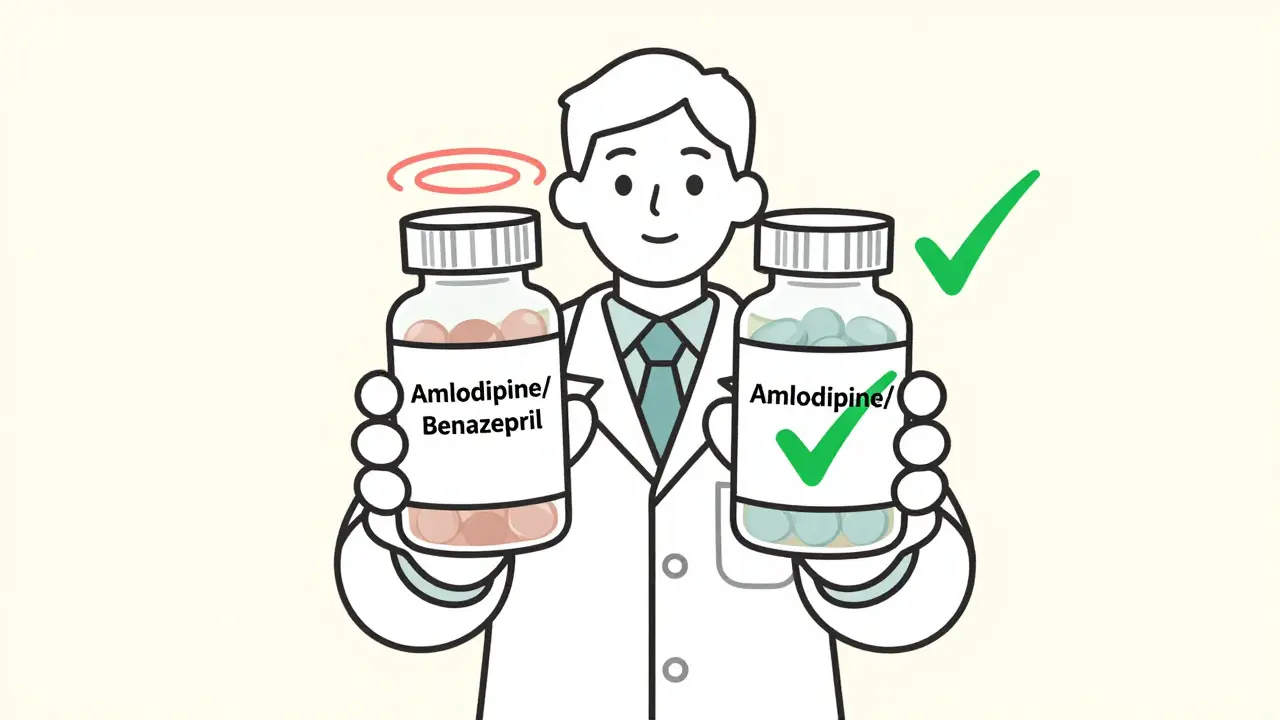

Inactive ingredients-fillers, dyes, coatings-seem harmless. But they can change how fast a drug dissolves. Rivaroxaban, a blood thinner, has seven generic versions, all rated "A." But three use croscarmellose sodium as a disintegrant; four use sodium starch glycolate. In a single-drug setting, that might not matter. In a combo with another NTI drug? It can delay absorption enough to cause a stroke or bleed. Pharmacists aren’t to blame. They’re following the rules. But the rules don’t account for real-world complexity. A pharmacist on Reddit shared that in just six months, they made three dosing errors switching between different strengths of amlodipine/benazepril combos. Patients got too much or too little. No one noticed until their blood pressure spiked or dropped dangerously. Another case: a patient switched from Vytorin (ezetimibe/simvastatin) to a generic. Their LDL cholesterol jumped 15%. The generic met all FDA standards. But the formulation changed how the drugs were absorbed together. The doctor didn’t know to check. The patient didn’t feel different-until their next lab test.What Works: Safe Practices for Clinicians

There are ways to reduce these risks. Hospitals that train staff for 40+ hours on therapeutic equivalence cut substitution errors by 65%. That’s not magic. It’s awareness. Key steps:- Always check the Orange Book TE code-not just the brand or generic name.

- For NTI combinations, avoid switching unless absolutely necessary.

- Use barcode scanning to confirm exact product before dispensing.

- Monitor patients for 72 hours after any switch, especially if they’re on blood thinners, seizure meds, or thyroid drugs.

- Keep a list of combo products with known formulation differences and flag them in your EHR.

The Bigger Picture: Where the System Fails

The generic drug market saves the U.S. healthcare system $1.7 trillion a decade. That’s huge. But the cost-cutting model assumes all "A" rated drugs are equal. They’re not. Combination products are the blind spot. The FDA is starting to catch on. Their 2023 draft guidance on complex combinations acknowledges that dose proportionality isn’t always linear. They’re even testing machine learning models to predict which substitutions might fail. Early results? 89% accurate. But until those tools are mandatory, we’re relying on outdated rules. And patients are paying the price.What’s Next?

The future may include "A*" ratings-special designations for combo products proven equivalent across multiple doses and formulations. Some experts are pushing for pharmacogenomic data to be part of equivalence decisions. Imagine a patient’s DNA telling you whether they metabolize one component faster than another. That’s not sci-fi. The NIH predicts 30% of therapeutic equivalence decisions will include genetic data by 2030. For now, the best defense is vigilance. Don’t assume equivalence means interchangeability. Don’t trust a rating alone. Ask: Is this a combo drug? Is it an NTI drug? Has it been switched before? Did the patient’s labs change after the switch? Because in combination therapy, the whole isn’t just the sum of its parts. Sometimes, it’s the difference between healing and harm.What does an "A" rating mean for combination drugs?

An "A" rating from the FDA means the combination product is considered therapeutically equivalent to the brand-name version. It has the same active ingredients, strength, dosage form, and route of administration, and meets FDA standards for bioequivalence. But it doesn’t guarantee identical effects in every patient, especially with complex combinations or narrow therapeutic index drugs.

Can generic combination drugs be safely swapped with brand-name versions?

For most patients and most combinations, yes. But for drugs with a narrow therapeutic index-like warfarin, levothyroxine, or phenytoin-swapping carries higher risk. Even small differences in how the drug is absorbed can lead to serious side effects. Always consult a clinician before switching, especially if the patient is on multiple meds.

Why do some generic combos cause changes in lab results?

Inactive ingredients like fillers and disintegrants can affect how quickly the active drugs are released. In a combination, this can alter the balance between components. For example, one generic might release simvastatin faster than another, leading to higher blood levels and a drop in LDL that’s too aggressive-or too slow. Lab changes don’t always mean the drug is unsafe, but they do mean the body is responding differently.

Are there combination drugs that should never be substituted?

Yes. Any combination containing a narrow therapeutic index (NTI) drug should be treated with caution. Examples include anticoagulants (warfarin), thyroid meds (levothyroxine), seizure drugs (phenytoin), and some psychiatric combinations. Even if they have an "A" rating, switching them without monitoring increases risk. Many experts recommend avoiding substitutions unless there’s no alternative.

How can pharmacists reduce errors with combination drug substitutions?

Pharmacists can reduce errors by: checking the Orange Book TE code before dispensing, using barcode scanning to confirm exact product, maintaining a list of high-risk combos with known formulation differences, and implementing a 72-hour follow-up protocol for patients switched on NTI combinations. Staff training reduces errors by over 60% in health systems that adopt these practices.

Comments

2 Comments

Solomon Ahonsi

Wow. So the FDA lets pharmacies swap life-saving meds like they’re trading baseball cards? And we wonder why people end up in the ER. This isn’t innovation-it’s negligence dressed up as cost-cutting.

Matt W

I’ve seen this firsthand. My grandma switched generics for her warfarin combo and ended up in the hospital with a bleed. The pharmacist swore it was ‘the same.’ Turns out, the filler changed how fast it dissolved. She’s fine now, but it took three months and three different labs to catch it. Don’t trust the sticker on the bottle.

Write a comment