SJS/TEN Medication Risk Checker

Check Medication Risk

This tool helps identify medications that may cause Stevens-Johnson Syndrome (SJS) or Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis (TEN). These are rare but life-threatening skin reactions that require immediate medical attention.

Most people take medication without a second thought. But for a tiny fraction of users, a common prescription can trigger a nightmare - a body-wide skin reaction so severe it can kill. Stevens-Johnson Syndrome (SJS) and Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis (TEN) are not just rare rashes. They’re medication-related emergencies that demand immediate hospital care. If you or someone you know develops a sudden, painful rash with blisters or mouth sores after starting a new drug, don’t wait. Go to A&E now.

What Exactly Are SJS and TEN?

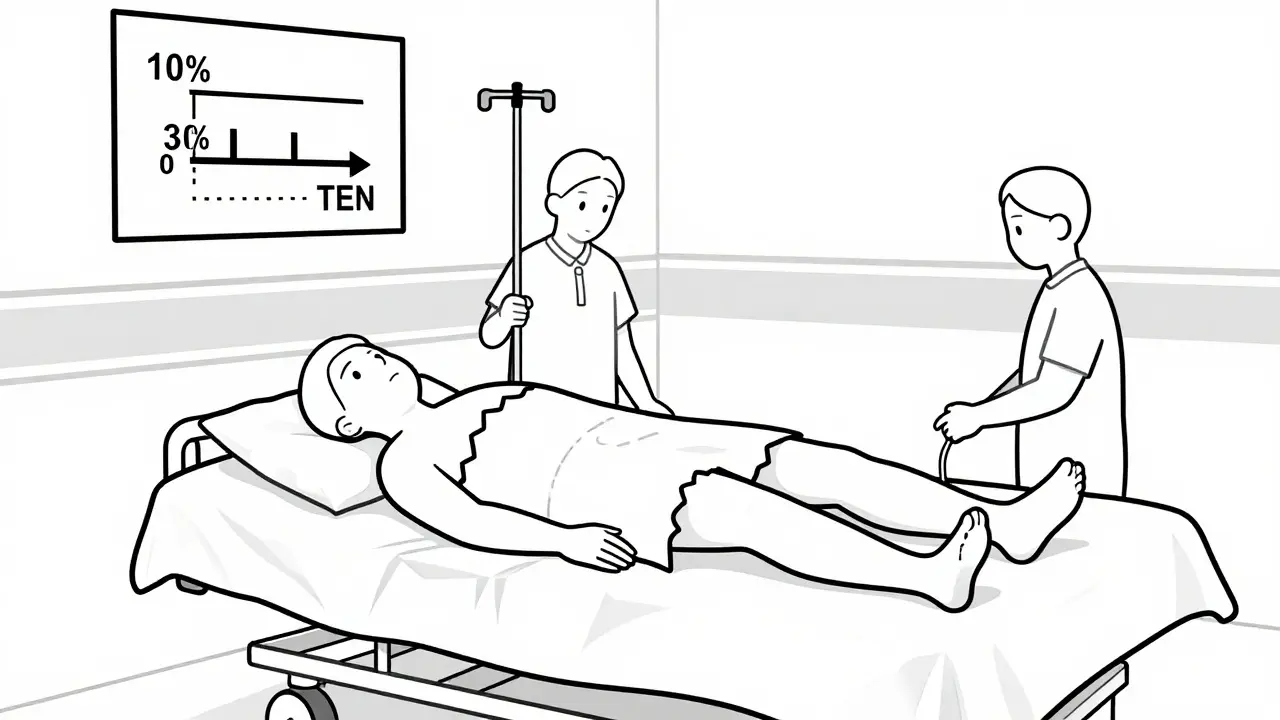

SJS and TEN are two ends of the same dangerous spectrum. They’re both severe skin reactions triggered by medications, where the top layer of skin starts dying and peeling off - like a bad burn, but from the inside out. The difference comes down to how much skin is affected.

If less than 10% of your body surface is involved, it’s classified as Stevens-Johnson Syndrome. If more than 30% is affected, it’s Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis. Between 10% and 30%? That’s overlap syndrome - still life-threatening. The skin doesn’t just get red. It blisters, breaks open, and sloughs away. Mucous membranes aren’t spared either. Sores form in the eyes, mouth, throat, genitals - anywhere the skin lines the inside of your body.

It starts like the flu: fever, sore throat, fatigue, burning eyes. Then, within one to three days, a red or purple rash appears. It spreads fast. Blisters form. Skin begins to peel. By the time you notice it’s serious, it’s already critical. This isn’t a case of “wait and see.” Every hour counts.

Which Medications Cause These Reactions?

Not every drug causes SJS or TEN - but some are far more dangerous than others. The list is small, but deadly. Allopurinol, used for gout, is one of the biggest culprits. So are anticonvulsants like carbamazepine, lamotrigine, phenytoin, and phenobarbital. Antibiotics like sulfamethoxazole (often in Bactrim) and nevirapine (for HIV) are also high-risk.

Even common painkillers can trigger it. Oxicam NSAIDs - meloxicam and piroxicam - have been linked to cases. And here’s the twist: if you’ve had a reaction to one drug in this group, you’re at risk for reacting to others in the same class. For example, if you had SJS from lamotrigine, you might also react to carbamazepine or phenytoin. Avoiding the exact drug isn’t enough. You have to avoid the whole family.

These reactions don’t always happen right away. They can show up days or even weeks after starting the drug. Or, strangely, after you’ve stopped it. Some people get a rash after restarting a medication they took before - especially if they stopped it suddenly and then went back to the same dose. That’s why doctors stress slow dose increases with lamotrigine, and why you’re told not to skip doses.

Who’s at Higher Risk?

Anyone can get SJS or TEN, but some people are more vulnerable. If you’ve had a skin reaction to epilepsy meds before, your risk goes up. Same if you’re allergic to trimethoprim. People with HIV or those on chemotherapy - anyone with a weakened immune system - are at greater risk. And if a close family member had SJS, your chances increase too. That points to a genetic link, especially with certain HLA gene variants.

Children are more likely to develop SJS than adults, though TEN is rarer in younger people. Taking sodium valproate along with lamotrigine also raises the risk. It’s not just the drug - it’s the combo.

And here’s the hard truth: if you’ve had SJS or TEN once, you’re at huge risk of getting it again - even from a different drug in the same class. Re-exposure can be fatal. That’s why survivors are given a medical alert bracelet and a detailed list of drugs to avoid for life.

What Happens in the Hospital?

There’s no magic pill for SJS or TEN. Treatment is about survival - stopping the damage and keeping you alive while your body heals.

First step: stop the drug. Immediately. No exceptions. Even if you’re not sure which one caused it, doctors will pull all suspect medications. Then, you’re moved to a burn unit or intensive care. Why? Because your skin is gone. You’re losing fluids, you’re vulnerable to infection, and your body is in shock.

Doctors treat you like a burn patient. IV fluids, pain control, wound care, and strict infection prevention. Antibiotics are used only if infection sets in - not as a blanket treatment. Steroids and IV immunoglobulins are sometimes tried, but evidence they help is weak. The best treatment? Time, and expert supportive care.

Recovery takes weeks - sometimes months. You might need feeding tubes if your mouth is too sore to eat. Eye care is critical. Without proper treatment, you could lose your vision. Many survivors need daily eye drops for years. Some develop permanent scarring in the eyes, throat, or genitals.

Long-Term Damage Is Real

Surviving SJS or TEN doesn’t mean you’re back to normal. The damage lingers. About 30 to 50% of survivors have lasting eye problems: dry eyes, light sensitivity, scarring, even blindness. Nails may fall off or grow back misshapen. Hair can thin out across the scalp. Skin may stay discolored or scarred.

Inside your body, things get worse. Esophageal strictures - narrowing of the food pipe - can make swallowing painful or impossible. Vaginal stenosis in women and phimosis in men can cause lifelong discomfort. Oral sores lead to gum disease and tooth loss. Some people develop chronic lung issues or kidney damage.

And yes, it can kill. Death usually comes from sepsis, organ failure, or blood clots. Mortality rates jump from 5% in SJS to over 30% in TEN. The longer you wait to get help, the higher the risk. Early diagnosis saves lives.

How to Prevent It

There’s no surefire way to prevent SJS or TEN - but you can reduce your risk.

- If you’re prescribed lamotrigine, carbamazepine, or allopurinol, ask your doctor about your risk. Genetic testing is available in some cases for high-risk groups.

- Never rush the dose. Lamotrigine, for example, must be started low and increased slowly. Skip steps, and you increase your chance of a rash turning deadly.

- Don’t start new medicines or supplements during the first 8 weeks of a high-risk drug. That’s when most reactions happen.

- If you get a rash - even a mild one - while on these drugs, contact your doctor immediately. Don’t assume it’s just “allergic.”

- Know your history. If you’ve had a rash with a drug before, tell every new doctor. Keep a list of drugs you’ve reacted to.

Most rashes from these drugs are harmless. But if it spreads, blisters, or hurts - especially with mouth or eye sores - treat it like an emergency. Don’t wait for your GP. Go to A&E. Call 999. This isn’t a “maybe.” It’s a now-or-never situation.

What to Do If You Suspect SJS or TEN

Here’s the checklist: If you’re on a high-risk drug and you notice:

- Flu-like symptoms (fever, sore throat, fatigue)

- A spreading red or purple rash

- Blisters on skin or inside mouth, eyes, or genitals

- Painful skin that peels easily

- stop the medication immediately. Go to the nearest emergency department. Bring your drug list. Tell them you suspect Stevens-Johnson Syndrome or Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis. Don’t wait for a referral. Don’t call your GP first. Time is skin. And skin is life.

Most people who survive SJS or TEN go on to live full lives - but they carry the scars, literally and figuratively. The key is acting fast. The more you know, the better your chance of stopping it before it’s too late.

Can Stevens-Johnson Syndrome be caused by over-the-counter drugs?

Yes. While most cases are linked to prescription drugs like anticonvulsants or antibiotics, over-the-counter NSAIDs like piroxicam and meloxicam have been documented as triggers. Even common painkillers like ibuprofen or naproxen - though rare - have been linked in isolated cases. Always consider any new medication, prescribed or bought without a prescription, as a potential cause if a severe rash develops.

Is Stevens-Johnson Syndrome contagious?

No. SJS is not contagious. It’s an immune-mediated reaction to a drug, not an infection. You can’t catch it from someone else. However, because it can be triggered by genetic factors, family members may share a higher risk - not because it spreads, but because they share similar genes that make them more susceptible to drug reactions.

How long does it take to recover from SJS or TEN?

Skin typically begins to regrow within 2 to 3 weeks, but full recovery can take months. Hospital stays often last 2 to 6 weeks. Long-term complications like eye damage, scarring, or organ issues may require ongoing care for years. Some people never fully regain normal skin texture or vision. Recovery isn’t just about healing skin - it’s about managing lifelong consequences.

Can you get SJS from vaccines?

Extremely rarely. While most cases are linked to medications, there have been isolated reports of SJS following certain vaccines, like the flu shot or hepatitis B vaccine. But the risk is far lower than from drugs like allopurinol or lamotrigine. The benefits of vaccination almost always outweigh this minimal risk. If you’ve had SJS before, talk to your doctor before getting any new vaccine.

Are there genetic tests to predict SJS risk?

Yes - for specific drugs and populations. For example, people of Asian descent taking carbamazepine are often tested for the HLA-B*15:02 gene variant, which greatly increases SJS risk. Similarly, testing for HLA-B*58:01 is recommended before starting allopurinol in certain groups. These tests aren’t routine for everyone, but if you have a family history or belong to a high-risk group, ask your doctor if testing is right for you.

What Comes Next?

If you’ve survived SJS or TEN, your care isn’t over. You need a plan. See a dermatologist for skin healing. See an ophthalmologist every 3 to 6 months for at least a year - eye damage can creep up slowly. A dentist or oral specialist can help with mouth sores and gum health. If you have genital scarring, a gynecologist or urologist should be part of your team.

Carry a medical alert card or bracelet listing every drug you can never take again. Update it every time you see a new doctor. Teach your family what to look for - because next time, you might not be able to speak for yourself.

Stevens-Johnson Syndrome and Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis are rare. But when they strike, they strike hard. Knowing the signs, the triggers, and the urgency can make the difference between life and death - not just for you, but for someone you love.

Comments

8 Comments

Dee Humprey

I saw a friend go through this after starting lamotrigine. One day she was fine, next day her skin was peeling off like a sunburn. They had to put her in a burn unit. Never take a rash on these meds lightly. Go to ER. Now.

John Wilmerding

It is imperative to emphasize that the clinical presentation of Stevens-Johnson Syndrome and Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis necessitates immediate cessation of all potentially causative pharmaceutical agents. Delay in intervention significantly correlates with increased mortality risk. Medical personnel must be educated to recognize the prodromal symptoms without delay.

Siobhan Goggin

This is such an important post. I wish more people knew how fast this can escalate. My cousin survived TEN but lost her vision in one eye. She says if she’d gone to the hospital two hours earlier, it might’ve been different.

mark etang

The empirical evidence supporting early intervention in SJS/TEN cases is unequivocal. Delayed diagnosis and continued exposure to inciting agents constitute a critical failure in clinical management. Hospitals must implement rapid-response protocols for suspected cases.

Ethan Purser

I swear this is what happens when you let Big Pharma control your medicine. They push these drugs like candy, then act shocked when people die. They don’t care. They just want your money. I bet they knew about the HLA link for years and buried it. Someone should sue them into oblivion. This isn’t medicine, it’s a slaughterhouse with a stethoscope.

Roshan Aryal

In India we don’t have this problem because we don’t take western pills like candy. My uncle took allopurinol for 15 years and never had an issue. This is just another American overreaction. You people panic over a rash like it’s the end of the world. We have real problems here - hunger, clean water, not your drug-induced skin meltdowns.

Vicki Yuan

I’m a pharmacist and I’ve seen this too many times. Patients assume a mild rash is "just an allergy" and keep taking the drug. The moment they see blistering or mucosal involvement, stop the medication and go to the ER - no exceptions. Also, if you’ve had a reaction to one drug in a class, avoid the whole class. Genetic testing isn’t perfect, but it’s better than risking death.

Uzoamaka Nwankpa

I lost my brother to this. They told him it was just a rash. He waited three days. By the time they admitted him, his organs were shutting down. I don’t even know how to talk about it. I just want people to know - if you feel something is wrong, don’t wait. Don’t be polite. Don’t call your doctor. Just go.

Write a comment