The WHO Model List of Essential Medicines isn’t just a list of drugs. It’s the global blueprint for what every health system - no matter how poor or remote - should have on hand to save lives. First published in 1977, this list has shaped how over 150 countries decide which medicines their people can actually get. And at its heart? Generics. Not because they’re cheap, but because they work, and they’re the only way millions can access life-saving treatment.

What the WHO Model List Actually Does

The WHO doesn’t sell medicines. It doesn’t run hospitals. But it does set the standard for what every country should consider essential. The 2023 version includes 591 medicines covering 369 conditions - from antibiotics for pneumonia to insulin for diabetes, from antiretrovirals for HIV to painkillers for childbirth. Roughly half of them are generics. That’s not an accident. It’s the core strategy.

The list splits medicines into two groups: core and complementary. Core medicines are the basics - things you should find in every village clinic. Complementary ones need more support - specialist staff, lab tests, monitoring. But both are chosen on one rule: if it doesn’t save lives, prevent disease, or ease suffering at a price a country can afford, it doesn’t make the cut.

This isn’t a wish list. Every medicine on the list has been vetted with hard data. It needs proof from clinical trials (Level 1a or 1b), clear evidence it’s better or cheaper than alternatives, and it must treat a disease that affects at least 100 people per 100,000. No lobbying. No brand names pushing for space. Just science and need.

Why Generics Are the Foundation

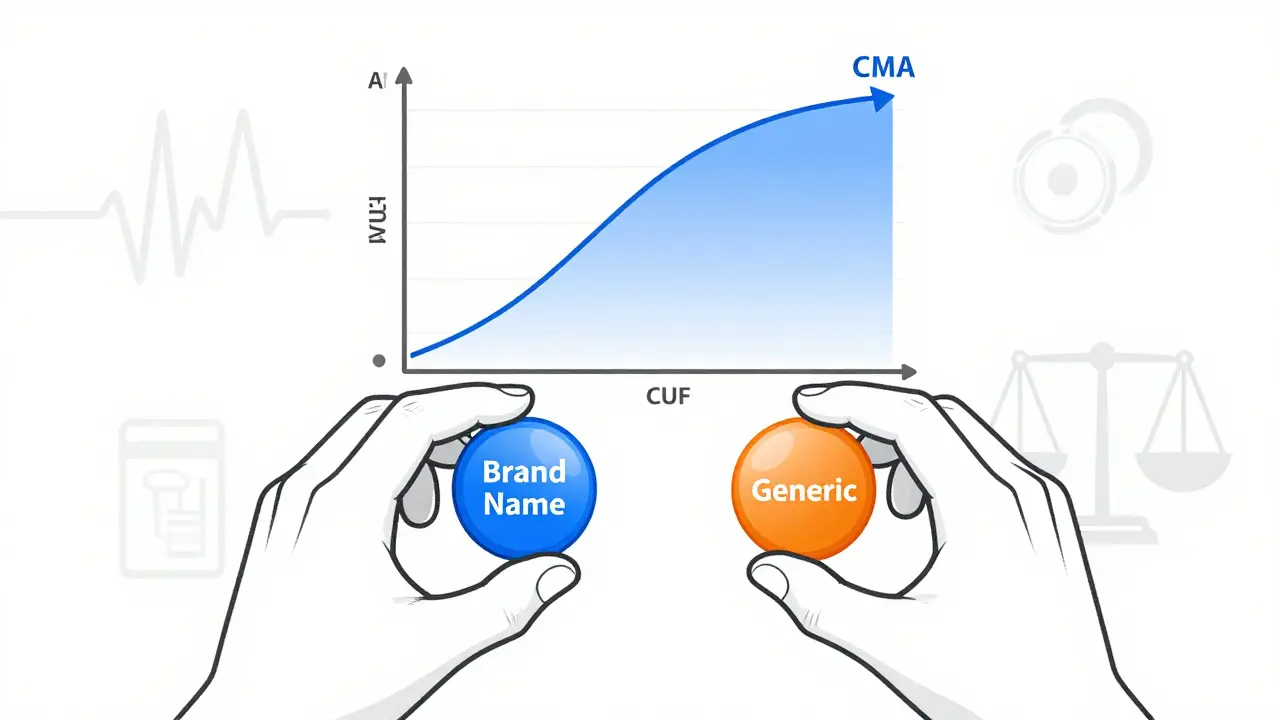

Let’s be clear: the WHO doesn’t care if a drug is branded or generic. It cares if it works and if it’s affordable. That’s why 273 of the 591 medicines on the 2023 list are generics. And those aren’t just any generics. They have to meet WHO Prequalification standards - meaning they’ve passed the same quality tests as the original branded version. That’s not easy. It requires bioequivalence studies showing the generic delivers the same amount of drug into the bloodstream within 80-125% of the original. For narrow-window drugs like warfarin or lithium? Even tighter: 90-111%.

Why does this matter? Because in places like rural Ghana or northern Nigeria, people don’t have the luxury of choosing between expensive brand-name drugs and cheaper knockoffs. They need to know the $0.10 pill they’re given is just as safe and effective as the $5 one. The WHO’s standards make that possible.

The results? HIV antiretrovirals dropped from $1,076 per patient per year in 2008 to just $119 today. That’s an 89% price drop - and it’s why 29.8 million people are now on treatment, up from 800,000 in 2003. That’s not magic. That’s generics, scaled globally because the WHO said: this is what works, and this is what we can afford.

How It’s Different From Hospital or Insurance Formularies

Don’t confuse the WHO Model List with your local hospital formulary or Medicare Part D. They’re not the same thing.

In the U.S., insurance formularies are about cost-sharing: Tier 1 = cheap, Tier 5 = expensive. They’re designed to steer patients toward cheaper options - often by making the good ones harder to get. The WHO doesn’t do tiers. It doesn’t care how much you pay out of pocket. It only asks: is this medicine necessary? Does it save lives? Can it be made reliably and affordably?

And while U.S. formularies must include at least two drugs per therapeutic category (to give insurers leverage), the WHO often lists just one. Why? Because sometimes, the evidence is so clear there’s no need for alternatives. For example, amoxicillin for childhood pneumonia. It’s cheap, safe, effective. No other antibiotic does it better at that level. So the WHO picks one - and that’s it.

Hospital formularies in high-income countries may reference the WHO list for global health programs, but 89% of U.S. pharmacy directors rely on domestic tools like Micromedex. The WHO list doesn’t replace local rules - it informs them. It’s the starting point, not the finish line.

Where It Works - and Where It Falls Short

There are success stories. In Ghana, adopting the WHO list led to a 29% drop in out-of-pocket medicine spending between 2018 and 2022. Pharmacists reported better availability of generics for hypertension and diabetes. In India, hospitals cut antimicrobial costs by 35% by switching to WHO-recommended antibiotic tiers.

But it’s not all smooth. In Nigeria, only 41% of essential medicines on the national list were consistently available. Stockouts lasted an average of 58 days per drug. Why? Not because the list was wrong - because the supply chain broke. No electricity to refrigerate vaccines. No trucks to deliver pills. No trained staff to manage inventory. The WHO list can’t fix that.

And there’s another problem: substandard drugs. WHO surveillance found that 10.5% of essential medicine samples in low- and middle-income countries were fake or poorly made - mostly antibiotics and antimalarials. Even if the list says “use this generic,” if the local pharmacy stocks a counterfeit version, it’s useless. The WHO can set standards, but it can’t police every pharmacy in every village.

Industry Impact and Global Shifts

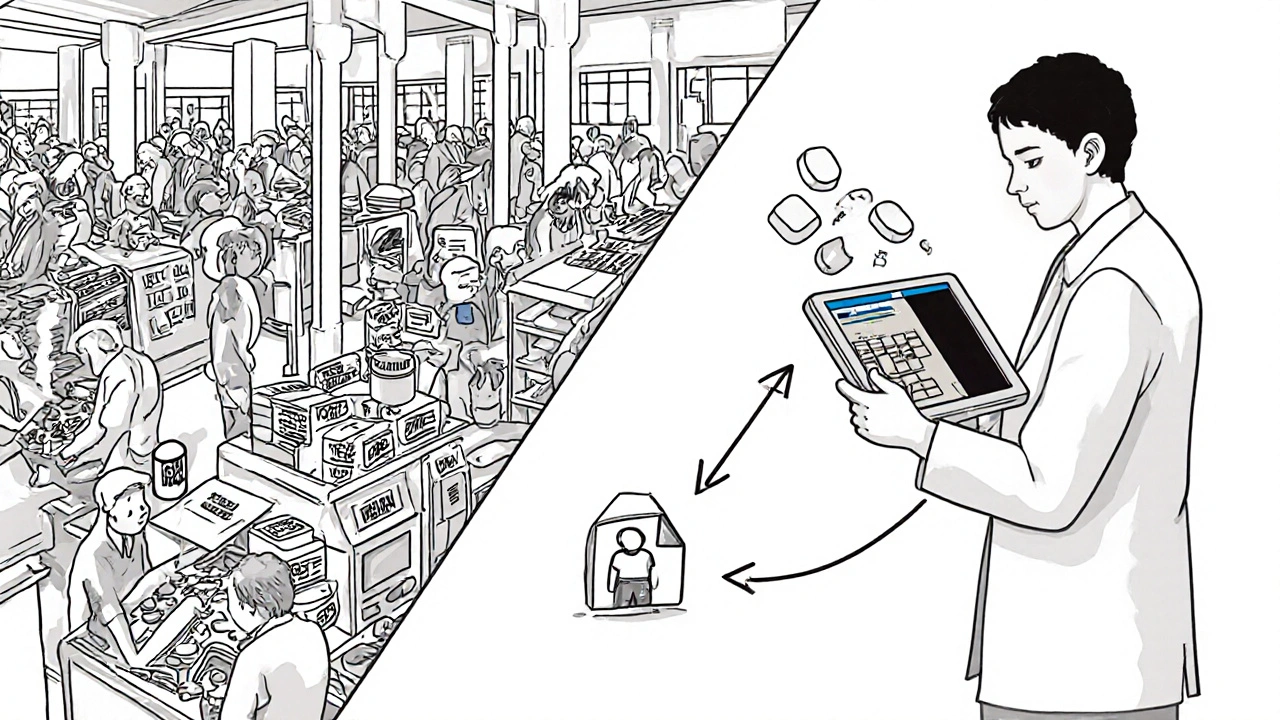

The WHO list has reshaped the global generics market. Since 2018, the number of WHO-prequalified generic products has jumped 47%. Why? Because if you want to sell to UN agencies, the Global Fund, or governments in Africa and Southeast Asia, you need that stamp. It’s the golden ticket.

Today, 63 countries recognize WHO Prequalification as good enough to skip their own testing. That’s up from 41 in 2018. It’s cutting red tape and speeding up access.

But the market is lopsided. 78% of generic medicine production comes from just three countries: India, China, and the U.S. That’s efficient - until a pandemic hits. In 2020-2022, 62% of low-income countries faced shortages of essential antibiotics because supply chains snapped. The WHO knows this. That’s why the 2023 list added new guidance on diversifying suppliers and building local manufacturing capacity.

What’s New in 2023 - and What’s Coming

The 2023 update wasn’t just a refresh. It was a shift. For the first time, it included seven biosimilars - copies of complex biologic drugs like monoclonal antibodies used in cancer and autoimmune diseases. That’s huge. These used to be too expensive for low-income countries. Now, with WHO backing, they’re being considered as viable options.

Forty-two percent of listed medicines now come in pediatric formulations - child-friendly syrups, dispersible tablets, smaller doses. That’s up from 29% in 2019. Before, kids often got crushed adult pills. Now, the list demands safe, accurate dosing for children.

And there’s a new app - the WHO Essential Medicines App - downloaded 127,000 times in 158 countries. Pharmacists in Malawi, doctors in Bolivia, nurses in Bangladesh use it to check what’s on the list, find dosage info, and see which generics are prequalified. It’s simple. It’s free. It’s changing practice on the ground.

Future updates will tie the list even closer to antimicrobial resistance. New draft guidelines require formularies to classify antibiotics into “stewardship tiers” - reserving the strongest ones for only the most serious cases. That’s not just about access - it’s about preserving what we have.

The WHO’s goal by 2030? Get essential medicine availability in primary care facilities from 65% to 80%. That’s ambitious. But it’s the only way to reach the UN’s goal of Universal Health Coverage.

The Big Picture

The WHO Model List isn’t perfect. It’s slow to add new drugs - only 12% of novel medicines approved between 2018 and 2022 made the 2023 list. Critics say it’s too cautious. Others worry about industry influence - 45% of the evidence used in 2023 came from industry-funded trials, up from 28% in 2015. The WHO now requires full financial disclosures from its experts, and they say compliance is 100%.

But here’s what no one can argue: without this list, millions wouldn’t have access to basic medicines. The WHO didn’t invent generics. But it gave them legitimacy. It gave them scale. It turned a patchwork of local efforts into a global movement.

It’s not about drugs. It’s about justice. About a child in rural Malawi getting antibiotics. A mother in Bangladesh getting insulin. A man in Uganda getting HIV treatment. The WHO Model List says: these aren’t privileges. They’re rights. And generics? They’re the tool that makes those rights real.

Is the WHO Model List legally binding for countries?

No, it’s not legally binding. Countries choose whether to adopt it. But over 150 have created their own National Essential Medicines Lists based on it. It’s the most widely used global standard, even if it’s not law.

Why does the WHO focus so much on generics?

Because generics are the only way to make life-saving medicines affordable at scale. Brand-name drugs often cost 10 to 100 times more. For countries with limited budgets, generics aren’t optional - they’re essential to reach everyone.

Are all generics on the WHO list safe?

Only those that meet WHO Prequalification standards are included. These undergo strict testing for quality, potency, and bioequivalence. But once a medicine leaves the manufacturer, local supply chains can introduce fake or substandard products - which the WHO can’t control.

How often is the WHO Model List updated?

Every two years. The last update was in July 2023. The next is expected in 2025. The process involves 25 independent experts reviewing hundreds of applications based on public health need, safety, and cost-effectiveness.

Can high-income countries benefit from the WHO Model List?

Absolutely. Even in wealthy countries, drug prices are a burden. The WHO’s focus on cost-effectiveness helps hospitals and insurers identify high-value generics. Some U.S. and European health systems use it to guide procurement for global programs or to benchmark their own formularies.

What’s the biggest challenge in implementing the WHO list?

It’s not the list - it’s the supply chain. Even with perfect guidelines, if there’s no power to refrigerate vaccines, no trucks to deliver pills, or no trained staff to manage stock, medicines won’t reach patients. The WHO now spends more time on implementation than ever before, because knowing what to use isn’t enough - you need to be able to get it.

For countries serious about health equity, the WHO Model List isn’t a suggestion. It’s a roadmap. And generics? They’re the engine that keeps it moving.

Comments

11 Comments

Christina Abellar

This is one of those rare posts that actually makes you feel hopeful. 🙏 Generics aren’t sexy, but they’re the quiet heroes keeping kids alive in places no one talks about.

Eva Vega

The WHO Model Formulary represents a paradigmatic shift in pharmaceutical prioritization, leveraging evidence-based pharmacoeconomic modeling to optimize therapeutic access across resource-constrained health systems. The bioequivalence thresholds (80–125%) are particularly salient in ensuring pharmacokinetic fidelity, thereby mitigating therapeutic failure risks in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs).

Margo Utomo

So let me get this straight - we’re talking about a $0.10 pill saving lives while Big Pharma laughs all the way to the bank? 😤💊

And now they’re adding biosimilars? Baby, that’s not progress - that’s justice with a pulse. 🌍❤️

George Gaitara

Wait - so you’re telling me the WHO just picks one drug and says ‘this is it’? No alternatives? That’s not science - that’s authoritarianism disguised as public health. And don’t even get me started on India manufacturing 78% of the world’s generics. This isn’t a list - it’s a cartel.

Deepali Singh

The data is cherry-picked. 89% price drop on ARVs? Sure - but only because they replaced patented drugs with generics that had no R&D cost. Meanwhile, innovation stagnates. The real cost is in the long-term erosion of pharmaceutical R&D incentives. You can’t have equity without sustainability.

Sylvia Clarke

They didn’t just make generics acceptable - they made them sacred. 🤯

Imagine a world where a child in Malawi gets the same medicine as a child in Manhattan - not because of wealth, but because someone decided that life shouldn’t come with a price tag. This list? It’s the closest thing we have to a moral compass for global health. And yes, it’s messy. And yes, supply chains break. But at least we’re trying to fix the system - not just the symptoms.

Jennifer Howard

I find it deeply concerning that the World Health Organization, an entity with no democratic mandate, is effectively dictating medical protocols to sovereign nations. Furthermore, the fact that 45% of the evidence cited in the 2023 update originated from industry-funded trials - despite the WHO’s public assurances - raises serious questions regarding conflicts of interest. This is not transparency. This is institutionalized influence peddling under the guise of humanitarianism. The public must be vigilant.

Abdul Mubeen

Let’s be honest - this entire framework is a distraction. The WHO doesn’t care about health equity. They care about control. The real agenda? To centralize pharmaceutical power under UN oversight, while quietly enabling China and India to monopolize production. The supply chain failures? Deliberate. It keeps poor countries dependent. The ‘prequalification’ stamp? A Trojan horse for global governance. Wake up.

mike tallent

Just saw a nurse in rural Zambia use the WHO app to check a dosage for a kid with pneumonia. She smiled and said, ‘This is the first time I didn’t have to guess.’ 🤝

That’s what this is. Not politics. Not profit. Just someone getting the right pill at the right time. Keep doing the work, WHO. We see you.

Joyce Genon

Look, I get the emotional appeal - ‘generics save lives,’ yada yada - but let’s not pretend this is some flawless utopian blueprint. The WHO list ignores drug resistance patterns, fails to account for regional disease variations, and has zero flexibility for local clinical expertise. In places like the American South, where opioid use is rampant and co-infections are common, following the WHO list blindly could mean missing critical comorbid treatments. And don’t even get me started on the fact that ‘core’ medicines aren’t always the most effective - sometimes the ‘complementary’ ones are the only ones that work for complex cases. This isn’t a solution - it’s a one-size-fits-all trap dressed up as compassion. The data they cite? It’s all from controlled trials in ideal conditions. Real-world medicine is messy. The WHO ignores that. And that’s dangerous.

Matt Wells

While the preceding commentary on supply-chain logistics is not without merit, one must acknowledge that the WHO Model Formulary operates as a normative instrument, not a regulatory one. Its efficacy is contingent upon domestic institutional capacity - a variable that cannot be externalized. To conflate the absence of cold-chain infrastructure with the inadequacy of the model is to commit a category error. The list remains a paragon of evidence-based prioritization, irrespective of implementation failures attributable to governance deficits.

Write a comment