Every year, millions of people end up in hospitals not because their illness got worse, but because the drugs meant to help them caused harm. These are called adverse drug reactions - and they’re not random. A growing body of evidence shows that your genes play a huge role in whether a medication will work safely for you. This is where pharmacogenomics comes in - the science of how your DNA affects how your body handles drugs. It’s not science fiction. It’s already changing how doctors prescribe medications, especially when patients are on multiple pills.

Why Your Genes Matter More Than You Think

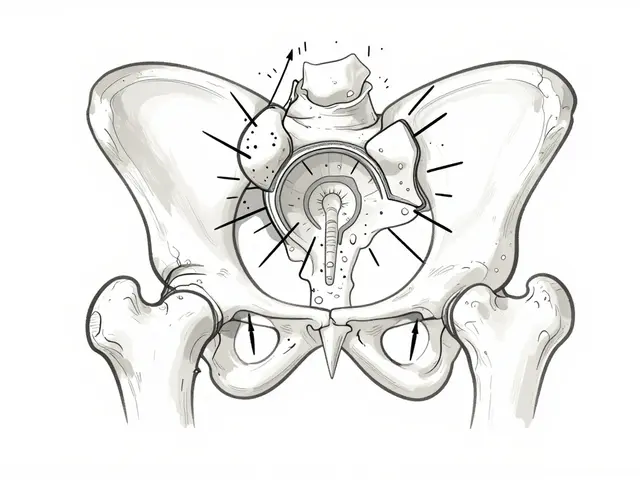

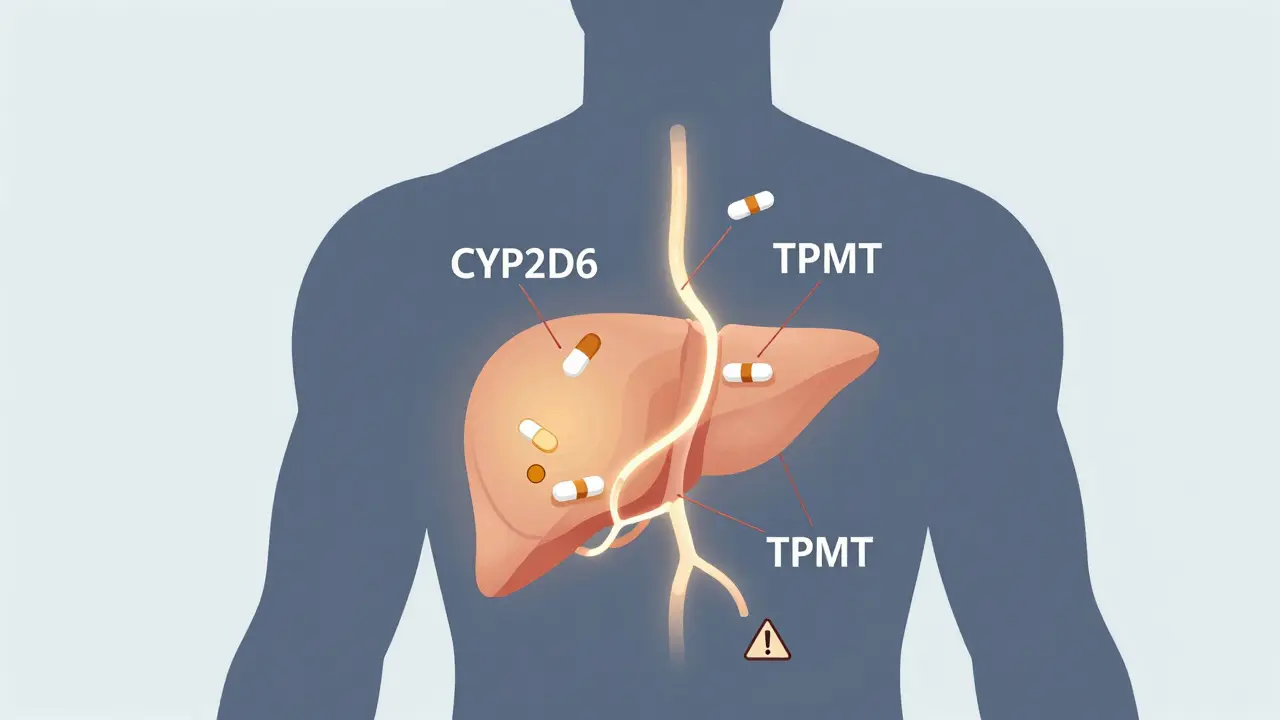

Most people think drug interactions happen because two medications clash - like when grapefruit juice stops a cholesterol drug from breaking down. That’s true. But it’s only half the story. Your genes determine whether your liver can even process those drugs in the first place. For example, the CYP2D6 gene controls how your body metabolizes about 25% of all prescription drugs - including antidepressants, painkillers, and heart medications. Some people have a version of this gene that makes them ultra-rapid metabolizers. They clear drugs too fast, so the medicine doesn’t work. Others are poor metabolizers. Their bodies can’t break down the drug at all, leading to dangerous buildup. The FDA lists over 140 gene-drug pairs with clear clinical implications. Take TPMT, a gene that affects azathioprine, a drug used for autoimmune diseases. If you’re a poor metabolizer, standard doses can destroy your bone marrow. But if you get tested first, your doctor can cut your dose by 90% and keep you safe. This isn’t theoretical. It’s in the drug label. And yet, most doctors still prescribe the same dose to everyone.Drug Interactions Get Worse When Genes Are Ignored

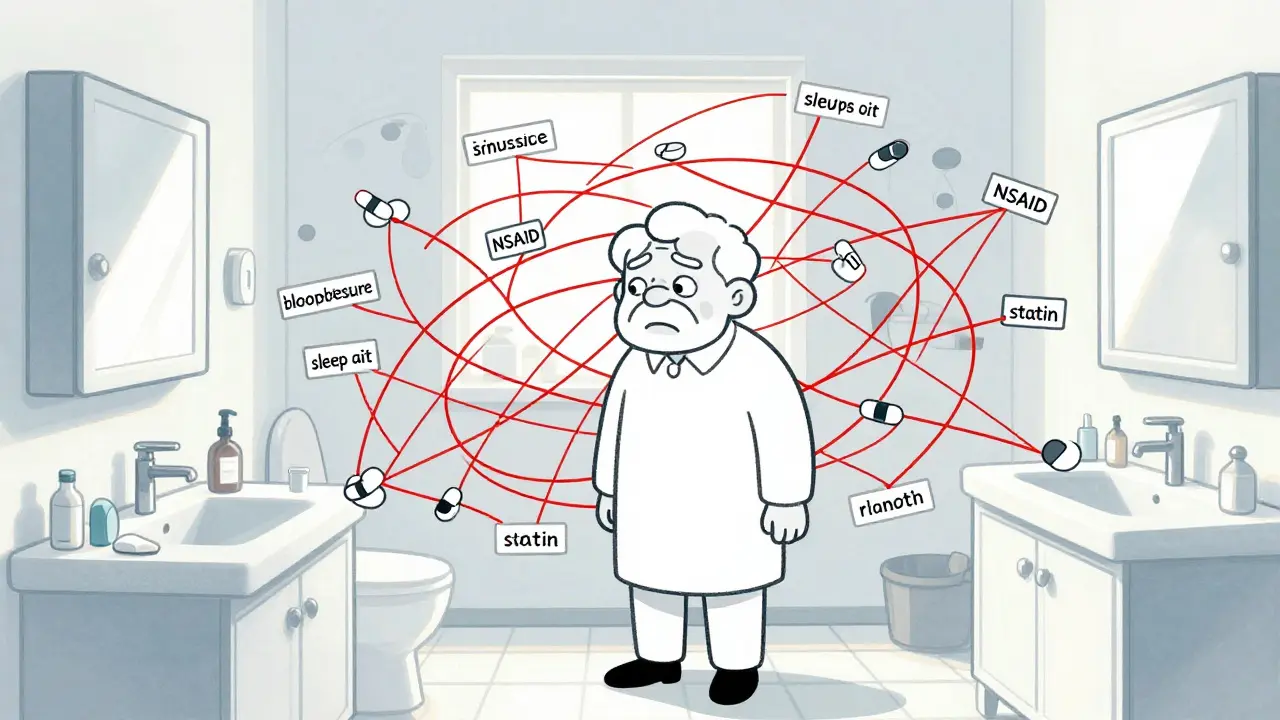

Imagine you’re taking an antidepressant that’s broken down by CYP2D6. You’re also on a common painkiller like tramadol, which is also processed by the same enzyme. If you’re a normal metabolizer, your body handles both fine. But if you’re a poor metabolizer, both drugs pile up. Your risk of serotonin syndrome - a potentially deadly condition - goes way up. Traditional drug interaction checkers won’t catch this. They see two drugs and flag the combo. They don’t know your genes. And that’s the gap. A 2022 study in the American Journal of Managed Care looked at over 1,000 patients in community pharmacies. When they added genetic data to the usual drug interaction screens, the number of high-risk interactions jumped by 90.7%. That’s not a small bump. That’s a seismic shift. It means half the interactions flagged by standard tools are either false alarms or missing critical genetic risks. The real danger? You might be taking a drug that’s perfectly safe for most people - but deadly for you because of your DNA.Phenoconversion: When Drugs Trick Your Genes

There’s another twist. Sometimes, drugs don’t just interact with each other - they change how your genes behave. This is called phenoconversion. Let’s say you have a genetic profile that makes you a fast metabolizer of CYP2D6. That means you normally clear certain drugs quickly. But if you start taking a strong CYP2D6 inhibitor - like fluoxetine (Prozac) or bupropion (Wellbutrin) - your body suddenly behaves like a poor metabolizer. Your genes haven’t changed. But your metabolism has. And if your doctor doesn’t know you’re on both drugs, they might increase your dose, thinking you’re not responding. That’s when toxicity hits. This isn’t rare. A 2020 study in Clinical Pharmacology & Therapeutics found that nearly 1 in 5 patients on multiple medications experience phenoconversion. The risk is highest in older adults taking five or more drugs - a group that’s grown to 13% of U.S. adults. For them, pharmacogenomics isn’t optional. It’s a safety net.

What the Evidence Says About Real Results

The numbers don’t lie. A 2022 meta-analysis of 42 studies, published in JAMA Network Open, found that when doctors used pharmacogenomics to guide treatment, adverse drug reactions dropped by 30.8%. Treatment success rates went up by 26.7%. For warfarin, a blood thinner with a narrow safety window, PGx-guided dosing reduced dangerous bleeding events by 31%. For patients with HLA-B*15:02, a genetic marker linked to severe skin reactions, avoiding carbamazepine entirely prevents life-threatening conditions like Stevens-Johnson Syndrome. At Mayo Clinic, where they’ve been doing preemptive genetic testing since 2011, 89% of patients had at least one actionable gene-drug interaction. With alerts built into their electronic records, inappropriate prescribing dropped by 45%. That’s not just a win for safety - it’s a win for cost. Adverse drug reactions cost the U.S. healthcare system $30 billion a year. PGx doesn’t just save lives. It saves money.Why Isn’t Everyone Doing This?

If the benefits are so clear, why isn’t every hospital using it? The answer is messy. First, not every gene-drug pair has solid guidelines. Of the 148 pairs the FDA recognizes, only about 22% have official recommendations from the Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium (CPIC). Second, most clinics don’t have the tools. Only 15% of U.S. healthcare systems have PGx results integrated into their electronic health records. Pharmacists - the frontline workers who check for drug interactions - say 67% of them lack proper decision support systems. And only 28% feel trained to interpret the results. Then there’s the cost. A single PGx test runs $250-$400. Insurance doesn’t always cover it. Only 19 CPT codes exist for these tests, and reimbursement is inconsistent. Hospitals need to spend an average of $1.2 million to build the infrastructure - software, training, lab partnerships. That’s a big barrier for small clinics. Worse, the data isn’t equally representative. Over 98% of PGx research has been done in people of European descent. Only 2% of participants in these studies are of African ancestry. That means the guidelines might not work as well for Black, Hispanic, or Indigenous patients. If we roll this out without fixing that gap, we risk making health disparities worse.What’s Next? AI, Regulation, and Real Change

The future is already here. The NIH’s All of Us program has returned PGx results to over 250,000 people. The FDA is adding 24 new gene-drug pairs to its list in 2024. Companies like 23andMe now offer limited PGx reports to 12 million customers. And AI is stepping in. A 2023 study in Nature Medicine showed an AI model that included genetic data improved warfarin dosing accuracy by 37% compared to traditional methods. The European Medicines Agency now says pharmacogenomics is a key factor in reducing drug interaction risks. The U.S. is catching up. But real change needs three things: better integration into clinical workflows, more training for providers, and fairer data. It’s not enough to test genes. You need systems that tell doctors what to do with the results - in real time, during the prescription process.What You Can Do Today

If you’re on three or more medications - especially antidepressants, painkillers, or heart drugs - ask your doctor if pharmacogenomics testing makes sense for you. It’s not a one-time thing. Your genes don’t change. Once you know your profile, it applies to every future prescription. Some pharmacies offer PGx panels for under $200. If your doctor says no, ask for a referral to a clinical pharmacist who specializes in medication management. You don’t need to be a cancer patient or have a rare disease to benefit. If you’ve ever had a drug side effect you couldn’t explain - this could be why. The old model - one-size-fits-all dosing - is falling apart. Pharmacogenomics isn’t the future of medicine. It’s the necessary upgrade.What is pharmacogenomics?

Pharmacogenomics is the study of how your genes affect the way your body responds to medications. It helps predict whether a drug will work for you, how much you need, and whether you’re at risk for side effects. Unlike traditional drug interaction checkers, it looks at your unique genetic makeup to personalize treatment.

Which genes are most important for drug interactions?

The CYP2D6 and CYP2C19 genes are the most common. CYP2D6 affects 25% of all prescription drugs, including antidepressants, painkillers, and beta-blockers. CYP2C19 handles drugs like clopidogrel (Plavix), proton pump inhibitors, and some anti-seizure medications. Other key genes include TPMT (for chemotherapy drugs), VKORC1 (for warfarin), and HLA-B*15:02 (for carbamazepine).

Can drugs change how my genes work?

Yes. This is called phenoconversion. A drug can temporarily block or speed up how your liver processes another drug - making you act like a different metabolizer than your genes suggest. For example, taking fluoxetine (Prozac) with a CYP2D6 substrate can turn a fast metabolizer into a slow one. That’s why combining medications without knowing your genetics is risky.

Is pharmacogenomics testing covered by insurance?

Sometimes. Coverage varies by insurer and reason for testing. Many plans cover it for specific drugs like warfarin, clopidogrel, or certain antidepressants. Out-of-pocket costs range from $200 to $400. Some labs offer payment plans. Ask your doctor or pharmacist about billing codes - there are 19 CPT codes for PGx testing, but not all are reimbursed equally.

Should I get tested if I’m on multiple medications?

Yes, especially if you’re taking five or more drugs, have had unexplained side effects, or are on antidepressants, painkillers, blood thinners, or anti-seizure meds. Polypharmacy increases interaction risk by 30-40% - and your genes can turn a minor interaction into a life-threatening one. Testing once can protect you for life.

Are PGx results accurate for all ethnic groups?

Not yet. Most research has been done in people of European ancestry. Only 2% of PGx study participants are of African descent. This means guidelines may not apply well to Black, Hispanic, or Indigenous patients. Researchers are working to fix this, but until then, results should be interpreted with caution in diverse populations.

Comments

15 Comments

Jocelyn Lachapelle

This is the kind of info we need more of. My grandma almost got hospitalized from a drug combo no one thought to check. Genetics should be part of every prescription now. No more guessing games.

Sai Nguyen

America still thinks medicine is a luxury. In India, we've been doing this for decades with local labs and zero hype. Your system is broken.

Lisa Davies

YES!!! 🙌 I got tested after my rash from that antidepressant and learned I'm a slow CYP2D6 metabolizer. My doctor changed my meds and I finally feel like myself again. This isn't sci-fi-it's survival.

Benjamin Glover

Fascinating. Though one must wonder if this is just another profit-driven fad masked as precision medicine. The data is compelling, but the infrastructure costs suggest this is for the elite.

Michelle M

It’s funny how we’ve spent centuries treating people like they’re all the same machine. We fix cars with specific parts, but we still give pills like they’re cookies from a bulk bag. Maybe it’s time we stopped pretending biology is a one-size-fits-all product.

Jake Sinatra

The clinical evidence presented here is robust and aligns with current guidelines from CPIC and FDA. However, implementation barriers remain significant. Systemic change requires policy reform, not just individual patient advocacy.

RONALD Randolph

This is exactly why we need to stop letting unqualified people prescribe meds! You can't just hand out pills like candy and expect people to survive. Genetic testing isn't optional-it's mandatory. And if your doctor doesn't know this, they're dangerous.

Melissa Taylor

I work in a community pharmacy and we just started offering PGx counseling. The patients are so relieved. One woman cried because she finally understood why she'd been sick for years on meds that 'should've worked'. This isn't just science-it's dignity.

Christina Bischof

I've been on 6 meds for years and never thought to ask about genes. Now I'm scared to even take my blood pressure pill. Maybe I should get tested... but I don't know who to ask.

John Samuel

The paradigm shift is undeniable. Pharmacogenomics represents the convergence of molecular biology, clinical informatics, and patient-centered care. The ethical imperative to integrate genomic data into therapeutic decision-making is not merely advantageous-it is non-negotiable in a just healthcare system.

Nupur Vimal

Everyone says this is great but no one talks about how most people can't afford it. My cousin got tested and it cost $300. She works two jobs. What's the point if only rich people get safe meds?

Cassie Henriques

Phenoconversion is the silent killer. CYP2D6 inhibition by SSRIs is massively underrecognized. I've seen patients on fluoxetine + tramadol crash into serotonin syndrome. The EHR alerts don't even flag it because they don't ingest genetic data. We're flying blind.

Raj Kumar

in india we have cheap tests now for like 1500 rs. my uncle got tested and his dose was cut by 80%. he was having side effects for 3 years. simple fix. why dont usa do this?

John Brown

I'm a nurse and I've seen this firsthand. A guy came in with liver failure because his pain meds piled up. Turns out he was a poor CYP2D6 metabolizer. He didn't know. His doctor didn't know. No one asked. We need this everywhere.

Mike Nordby

The underrepresentation of non-European populations in pharmacogenomic studies remains a critical flaw. Without equitable genomic data, precision medicine risks becoming precision inequity. This is not merely a scientific gap-it is a moral failure.

Write a comment